Meare Close House’s renovation

The original part of the house is reputed to date from the 1580s with major Victorian Gothic restyling in 1851. Modernisation took place in the 1930s and extension during the 1950s. Adjacent, though now forming a wing of the house, is what was formerly a two storey Victorian cottage. For over the last 70 years, the house has been owned and lived in by three generations of one family.

The original part of the house is reputed to date from the 1580s with major Victorian Gothic restyling in 1851. Modernisation took place in the 1930s and extension during the 1950s. Adjacent, though now forming a wing of the house, is what was formerly a two storey Victorian cottage. For over the last 70 years, the house has been owned and lived in by three generations of one family.

As the current owners are both local and friends of the previous owners, there is a great deal of information flowing regarding the house. The house spent its early life surrounded by farmland and in latter days by a plant nursery and though now surrounded by new build it is still a little haven in a village in the Green Belt of Surrey that is facing the onslaught of London from the North, Reigate and Crawley from the South.

Though the property did not have the benefit of any modern insulation material, it retained heat in the winter and was cool even on the hottest days in summer that implied the house was of sound construction. However, a mishmash of plastic, aluminium and cast iron guttering that was not sufficient for the water it had to carry was in danger of damaging the property. Internally, apart from requiring just a general up-dating, there appeared to be great potential to rediscover the original heart of the house behind the Victorian and 30s black paint, black stain and boxing in.

Though the property did not have the benefit of any modern insulation material, it retained heat in the winter and was cool even on the hottest days in summer that implied the house was of sound construction. However, a mishmash of plastic, aluminium and cast iron guttering that was not sufficient for the water it had to carry was in danger of damaging the property. Internally, apart from requiring just a general up-dating, there appeared to be great potential to rediscover the original heart of the house behind the Victorian and 30s black paint, black stain and boxing in.

Needing an empathetic approach, the architect Graham Ryding of Donovan Hewitt and consequently, builders Bryan Willamson & Daughters were appointed. A team that has worked closely to match the owners’ hopes whilst guiding to achieve the property’s full potential.

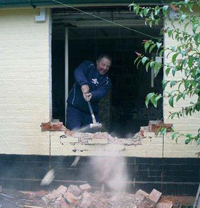

The relatively easy option was to work on the outside of the property first and lead to the discovery of some of the house’s construction history. Removing render from a Victorian wing exposed evidence of a demolished extension and two bricked up archways. Deciding to open up the archways for use, one as a door into the garden and the other a half window meant the skilful repair and matching of the brickwork in the arches. Though both an arched door and window were sourced from salvage companies they had to be adapted to fit and the art came in making even the custom built door frame, look as if it were the original Victorian features rather than replacements. The initial plan was to leave the roof untouched but an inspection hole revealed that untreated timber and rapidly rusting iron nails had been used for the slates. It transpired this was only relevant to the 1950s extension; the older roof was of much sounder construction. The roof space was fascinating with Elizabethan roof beams and partitions of raw wattle and terracotta coloured daub giving evidence of a possible second or third storey existing at some time. Rows of Elizabethan terracotta tiles confirmed that the roof had been lower and tiled and therefore the taller slate roof was probably part of the 1851 modernisation. Great care had to be taken to maintain the ventilation for the roof beams when replacing the slates.

The initial plan was to leave the roof untouched but an inspection hole revealed that untreated timber and rapidly rusting iron nails had been used for the slates. It transpired this was only relevant to the 1950s extension; the older roof was of much sounder construction. The roof space was fascinating with Elizabethan roof beams and partitions of raw wattle and terracotta coloured daub giving evidence of a possible second or third storey existing at some time. Rows of Elizabethan terracotta tiles confirmed that the roof had been lower and tiled and therefore the taller slate roof was probably part of the 1851 modernisation. Great care had to be taken to maintain the ventilation for the roof beams when replacing the slates.

Over the years, paths around the property had been built one on top of the other and for the benefit of the property some were lowered. This revealed the foundations and occasionally, the lack of foundations and damp course. Other manual general excavation lead to the discovery of underground pipes and drains that had been laid across one another and some that ran where a building had not existed when it was originally laid. In the process of rationalizing the pipe work, lead and broken terracotta pipes were replaced. The property was to be completely re-plumbed and re-wired and to maintain the integrity of the building, architect and builder were determined that it would all be hidden. Above left: Rafters raised to add height, all wood doff cleaned. Flint walls evened ready for kitchen units Floorboards, including some 12 and 14inch wide 17th century floorboards, were carefully lifted. Flint walls had to be drilled and false floors created. One ceiling was lowered to enable a soil pipe to be hidden and consequently avoid several yards of soil pipe appearing on the outside of the property.

The property was to be completely re-plumbed and re-wired and to maintain the integrity of the building, architect and builder were determined that it would all be hidden. Above left: Rafters raised to add height, all wood doff cleaned. Flint walls evened ready for kitchen units Floorboards, including some 12 and 14inch wide 17th century floorboards, were carefully lifted. Flint walls had to be drilled and false floors created. One ceiling was lowered to enable a soil pipe to be hidden and consequently avoid several yards of soil pipe appearing on the outside of the property.

The cast iron bath caused the building inspector great concern and for instating a replacement cast iron bath, reinforcement was hidden behind a platform that was integrated into the bathroom. The platform also enabled the original slope of the floor to remain as part of the character of the house.

Gradually all the floorboards were lifted and stored whilst rockwool was inserted for both insulation and soundproofing but in order to allow air circulation the rockwool had to be suspended. As some of the floorboards were to be left uncarpeted they were cleaned by hand to remove the dark stain but retain the patina of their age. The Victorian parquet floor in the hallway required some replacement pieces, cleaning and the use of contrasting waxes to highlight a compass that is built into the parquet.

The Victorian parquet floor in the hallway required some replacement pieces, cleaning and the use of contrasting waxes to highlight a compass that is built into the parquet.

Though the property had very little damp course provision, it did not suffer from damp except for two places. In a bedroom, closer examination showed an impervious concrete render to a height of 3ft was acting like a wick drawing water into the room. Once the cement render was removed and the walls dried out, lime plaster was used and the problem was solved. On the ground floor, again cement render proved to be the problem and had to be removed.

In the heart of the property, after some exploratory digging, the false ceiling was removed enabling the original beams to be re-discovered and exposing the white painted underside of the floorboards of the room above. This also lead to the discovery that the Victorian adaptation had removed the support structure of the side of the property. Though the side of the property had floated unsupported for about 158 years, acro props were inserted whilst matching beams were sourced. Years of experience meant builder had acro props on stand-by for any such discoveries. Across were also required when unearthing what was suspected to be an inglenook fireplace. There were about 4 or 5 generations of fireplace and it appears that during the 4th or 5th generation of fireplace, the main beam of the inglenook, though a solid 16in x 10in block of wood, had been or was being burnt at one end. The beam had to be extracted and a replacement beam sourced. When digging out the hearth, a 9” square terracotta tile was found and, at Bryan Williamson’s suggestion, a new hearth using similar 9” terracotta tiles were used based on a design at Hampton Court. Inside the chimney the metal meat hooks can be seen. The intention is to parge the chimney ready for open fires.

Across were also required when unearthing what was suspected to be an inglenook fireplace. There were about 4 or 5 generations of fireplace and it appears that during the 4th or 5th generation of fireplace, the main beam of the inglenook, though a solid 16in x 10in block of wood, had been or was being burnt at one end. The beam had to be extracted and a replacement beam sourced. When digging out the hearth, a 9” square terracotta tile was found and, at Bryan Williamson’s suggestion, a new hearth using similar 9” terracotta tiles were used based on a design at Hampton Court. Inside the chimney the metal meat hooks can be seen. The intention is to parge the chimney ready for open fires.

Behind a 1950s brick fireplace in a bedroom a second, though much smaller, inglenook was discovered. Two original wooden fireplace surrounds in the gothic revival style installed by the Victorian owner, were cleaned and given prominence in the Victorian part of the property. Further beams were exposed in an upstairs room on a wall that would originally have been on the outside of the property. This entailed the gentle removal of plaster and the repointing and lime washing of the brickwork. The apse marks on the beams had to be removed and the Jos method used to bring out the colour of the wood but retain all the age and imperfections of the natural wood.

Further beams were exposed in an upstairs room on a wall that would originally have been on the outside of the property. This entailed the gentle removal of plaster and the repointing and lime washing of the brickwork. The apse marks on the beams had to be removed and the Jos method used to bring out the colour of the wood but retain all the age and imperfections of the natural wood.

Subsequently, the Jos method was used to clean or remove black paint from the beams throughout the property.

The date of the Victorian modernisation is recorded on a plaque of partially exposed flint wall that bears the date 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition. More significantly when some very stubborn woodchip wallpaper was removed there was a layer of Victorian decorative wallpaper and under that was a copy of The Universal Register (now The Times) dated May 3, 1851. One of the headlines announces Mr Rossetti’s new poem. Unfortunately only fragments of the wallpaper and newspaper were rescued. Removal of vinyl wallpaper in a bedroom revealed a slightly damaged Victorian trompe l’oeil door with shadowing where, to add authenticity, a wood frame must once have existed. Damage to the trompe l’oeil has been restored.

Removal of vinyl wallpaper in a bedroom revealed a slightly damaged Victorian trompe l’oeil door with shadowing where, to add authenticity, a wood frame must once have existed. Damage to the trompe l’oeil has been restored.

Two decorative doors have been re-instated with old stain glass shaped to fit the doors’ unique shapes.

The adjacent Victorian 2 storey cottage had been destroyed by fire in the late 1940/50s. Possibly because of the shortage of materials at the time, the cottage was made into a single storey garage. In the 1970s, though it remained a garage it was joined to the main property. Its new life is to be a kitchen. The floor was dug out to inspect the foundations and to bring the floor to ground level. Where an up-and-over door was removed a flint facia was constructed to match the existing flint wall. The roof was removed and the current building regulations level of insulation inserted. Internally, the rafters and roof beams were raised and cleaned. Though the walls were thick flint walls, to meet building regulations a stud wall was erected and insulation added. The floor was laid with 12 in square handmade Burgess Hill clay tiles, the rejects of a batch made for St Paul’s Cathedral. A window into the rose garden was reinstated from one rescued from the main property.

Contact information:

Graham Ryding BSc Dip Arch (Lond) RIBA Donovon Hewitt

http://www.donovanhewitt.co.uk

Brian at B Williamson & Daughters

www.bwilliamsonanddaughters.co.uk

From Listed Heritage, the specialist magazine for the Listed Property Owners Club http://lpoc.co.uk/