The Clive Engine House, North Wales

The Clive Engine House is one of the few remaining such buildings in Wales. It was built to Cornish standards in 1862 but stands on ground that is thought to have been mined since Roman times. The Talargoch Mine produced copper, silver and calamine, but was best known for the extraction of lead ore.

The Clive Engine House is one of the few remaining such buildings in Wales. It was built to Cornish standards in 1862 but stands on ground that is thought to have been mined since Roman times. The Talargoch Mine produced copper, silver and calamine, but was best known for the extraction of lead ore.

In the late 1800s, Talargoch was one of the most productive mines for miles around as the advent of the coal-fired steam engine facilitated larger mines following longer veins and deper shafts to be sunk. One of these larger shafts was the Clive Shaft, sunk in 1845 to a depth of over 600ft and employing the labour of 350 men. The removal of water from the mines was originally the work of horses yoked to a circular whim, but mechanisation brought with it the Cornish beam engine and to house this industrial beast, the Cornish engine house was born. The Clive Engine House contained a hugely powerful 100-inch diameter cylinder engine powered by seven boilers pushing a pivoting beam which weighed some 85 tonnes, drawing tens of millions of pounds of water out of the shaft.

In the late 1800s, Talargoch was one of the most productive mines for miles around as the advent of the coal-fired steam engine facilitated larger mines following longer veins and deper shafts to be sunk. One of these larger shafts was the Clive Shaft, sunk in 1845 to a depth of over 600ft and employing the labour of 350 men. The removal of water from the mines was originally the work of horses yoked to a circular whim, but mechanisation brought with it the Cornish beam engine and to house this industrial beast, the Cornish engine house was born. The Clive Engine House contained a hugely powerful 100-inch diameter cylinder engine powered by seven boilers pushing a pivoting beam which weighed some 85 tonnes, drawing tens of millions of pounds of water out of the shaft.

Unfortunately for this engine house, it only saw twenty two years of service as the Talargoch Mine closed for good in 1884. The building was stripped out and the machinery sold off to other mines. Unusually, the roof was left on, but the building was otherwise left to the elements, quickly falling into a largely dilapidated state. However, the building was robustly built to take the huge forces of very powerful machinery, meaning it wasn’t going to give in to time too easily! The design of an engine house was fairly universal since they were built to accommodate a fairly standard machine. Their prevalence across the country and the rest of the world was such that nobody thought much of them until relatively few were left. Today, the Clive Engine House is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and Grade II listed and is considered to be a rare example of its type. The fate of the building had been the subject of much local concern for many years, particularly given that the engine house is the only remaining building still standing of the large complex originally on the site.

Unfortunately for this engine house, it only saw twenty two years of service as the Talargoch Mine closed for good in 1884. The building was stripped out and the machinery sold off to other mines. Unusually, the roof was left on, but the building was otherwise left to the elements, quickly falling into a largely dilapidated state. However, the building was robustly built to take the huge forces of very powerful machinery, meaning it wasn’t going to give in to time too easily! The design of an engine house was fairly universal since they were built to accommodate a fairly standard machine. Their prevalence across the country and the rest of the world was such that nobody thought much of them until relatively few were left. Today, the Clive Engine House is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and Grade II listed and is considered to be a rare example of its type. The fate of the building had been the subject of much local concern for many years, particularly given that the engine house is the only remaining building still standing of the large complex originally on the site.

In 2010 funding was identified by Cadw and Denbighshire County Council who applied for a £100,000 grant from the WREN Heritage Restoration Fund. WREN is a not for profit company that awards grants to community, conservation and heritage projects within a ten-mile radius of landfill sites, from funds donated by Waste Recycling Group (WRG) to the Landfill Communities Fund. Cadw and Denbighshire CC also put forward a percentage of the funding for the project. Conservation Architects Donald Insall Associates were appointed to draw up plans for the project, to develop the philosophical approach based on the significance of the building as a whole, and to consider the approach to the subsequent repair and conservation of each element of the fabric to achieve the wider conservation objectives.

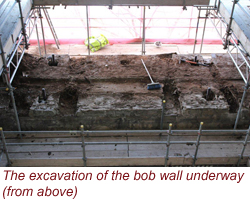

In January 2012, specialist historic building contractor Recclesia Ltd moved onto site and began to sort carefully through the years of detritus, vegetation, collapsed masonry and disintegrated historic building fabric. The entire building was tangled thick with ivy, self-seeded trees at low and high level, all wrapped around the remains of the roof and fallen masonry. The work was carried out under an EPS (European Protected Species) License granted by the Welsh Assembly Government as bats were known to have been roosting on site and all of the uncovering work was carried out under ecological watch. It took several weeks just to reveal the remains of the original building and sort through the salvageable fabric. One of the most difficult areas of the building to reveal was the top of the bob wall, the huge mounting wall that took the weight and the force of the pivoting beam over the shaft beneath.

In January 2012, specialist historic building contractor Recclesia Ltd moved onto site and began to sort carefully through the years of detritus, vegetation, collapsed masonry and disintegrated historic building fabric. The entire building was tangled thick with ivy, self-seeded trees at low and high level, all wrapped around the remains of the roof and fallen masonry. The work was carried out under an EPS (European Protected Species) License granted by the Welsh Assembly Government as bats were known to have been roosting on site and all of the uncovering work was carried out under ecological watch. It took several weeks just to reveal the remains of the original building and sort through the salvageable fabric. One of the most difficult areas of the building to reveal was the top of the bob wall, the huge mounting wall that took the weight and the force of the pivoting beam over the shaft beneath.

The bob wall top was excavated under archaeological watch and underneath a century of growth the original timbers and mounting brackets for the beam were discovered. The metalwork was largely intact and was quickly protected, but the timber mounting beams were rotten beyond saving and after a lot of discussion and consideration, the decision was made to remove them. However, rather than simply leave a gap, new oak beams were added onto the sides of the bob wall to help ensure that the visual impression of the original layout was not lost. The mounting metalwork was conserved and treated, and the wall head coated with an hydraulic lime weathering coat to help the bob wall to cope with the weather in its exposed location.

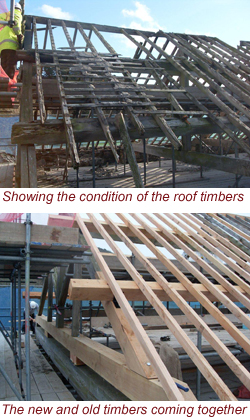

Above the bob wall the roof had failed entirely, timbers were very badly rotten, about two thirds of the slates were missing and the oak wall plates and masonry wall heads had failed entirely and disintegrated. All of the roof timbers were examined and tested and marked up for replacement or repair. Rather than replacing whole sections, new sections were spliced into the old in the same timber types, using a combination of joinery techniques and steel plates. The biggest exception to this was the bottom chord of the bob wall truss, which was some 30 feet long and 18 inches square in section and was hollow from end to end and required complete replacement. This massive timber was difficult to source and had to be installed by crane – at the same time as supporting the retained truss above whilst the new section was carefully manoeuvred into position ready to be spliced into the existing. The roof itself was re-slated using a combination of the original salvaged slates and reclaimed slates to match. The underside was torched using a lime putty mix designed to withstand both the heat and movement of the slates.

Above the bob wall the roof had failed entirely, timbers were very badly rotten, about two thirds of the slates were missing and the oak wall plates and masonry wall heads had failed entirely and disintegrated. All of the roof timbers were examined and tested and marked up for replacement or repair. Rather than replacing whole sections, new sections were spliced into the old in the same timber types, using a combination of joinery techniques and steel plates. The biggest exception to this was the bottom chord of the bob wall truss, which was some 30 feet long and 18 inches square in section and was hollow from end to end and required complete replacement. This massive timber was difficult to source and had to be installed by crane – at the same time as supporting the retained truss above whilst the new section was carefully manoeuvred into position ready to be spliced into the existing. The roof itself was re-slated using a combination of the original salvaged slates and reclaimed slates to match. The underside was torched using a lime putty mix designed to withstand both the heat and movement of the slates.

The Clive Engine House is one of a very few engine houses to have been plastered out internally, and a significant proportion of the plaster had survived on the walls. Further, the layout of the remaining plasterwork showed the location of original staircases, mountings and location points of the machinery on the inside. In order to preserve the legibility, painstaking work was carried out to conserve as much of the lime plasterwork by micro-pinning, grouting and weather-shedding the remaining perimeter of each area, followed by protective coats of limewash. The retention and conservation of this original fabric was one of the most successful and one of the most striking parts of the project on completion, allowing visitors to understand the original internal layout.

It is expected that visitor numbers will be quite high as the project generated a huge amount of public interest. There was a daily stream of visitors to site, all wanting to see the work going on and all wishing the project well. The building is such a prominent landmark and close to the main road, meaning that it is both very well known and that thousands of local people have watched it decay for their entire lives. Such was the level of interest that an open day was held to allow local people the chance to see the work underway. Some 120 people came through on three tours, but so many more wanted to come that a second open day had to be held a fortnight later. The days were hosted by County Archaeologist Fiona Gale who gave a fascinating talk about the history of the site and Jamie Moore from Recclesia, who gave a talk about the work in progress, the conservation approach and some of the specialist techniques being employed.

It is expected that visitor numbers will be quite high as the project generated a huge amount of public interest. There was a daily stream of visitors to site, all wanting to see the work going on and all wishing the project well. The building is such a prominent landmark and close to the main road, meaning that it is both very well known and that thousands of local people have watched it decay for their entire lives. Such was the level of interest that an open day was held to allow local people the chance to see the work underway. Some 120 people came through on three tours, but so many more wanted to come that a second open day had to be held a fortnight later. The days were hosted by County Archaeologist Fiona Gale who gave a fascinating talk about the history of the site and Jamie Moore from Recclesia, who gave a talk about the work in progress, the conservation approach and some of the specialist techniques being employed.

The completed building is very much a case study in how to conserve a building “as found”. The objective was not to restore the building to a specific point in its history, a bottomless can of worms for any conservator of historic buildings, but to save everything that was left and to conserve each element in the best possible way to secure its survival into the future. There were nevertheless plenty of conservation scruples to deliberate over, such as how best to secure the building without impinging upon the original fabric too heavily or how to allow visitors into an un-manned site without obscuring the appearance or intruding upon the original form of the entrances. In many ways, the success of the scheme executed here can be measured by the extent to which it looks like nothing has changed. The building is now very obviously in good repair, but this was much more an exercise in gently erasing a century of decay and of attending to the tiniest of details as well as the larger issues. The end result is a building which appears to have been recently vacated by the mining company that left in 1884.

• For More informatiion about Recclesia and more images on this project please visit www.recclesia.com.

Acknowledgements

Talargoch Mine by J.A. Thorburn (British Mining publication No.31, 1986)

Metal Mines of North Wales, CJ Williams, (Bridge, 1997)