English Church Clocks by Keith Scobie-Youngs

English Church Clocks, referred to as either tower or turret clocks are not simply over sized house clocks. They reach out over the entire community, having once provided a time standard to which all watches and house clocks could be set and appointments met. Long, complex connections beyond the movement drive hands exposed to wind, rain and snow.

English Church Clocks, referred to as either tower or turret clocks are not simply over sized house clocks. They reach out over the entire community, having once provided a time standard to which all watches and house clocks could be set and appointments met. Long, complex connections beyond the movement drive hands exposed to wind, rain and snow.

Wires pull heavy hammers to strike and chime bells in the belfry above, and still, in many cases, massive weights need to be wound weekly or daily to ensure everything operates as it should.

Today accurate time is readily available to us all. Every modern appliance seems to have its own built in clock and the amazing accuracy of quartz watches and their low price really means that the turret clock is no longer indispensable as an essential public timekeeper.

However, those who care for a turret clock will know well how highly regarded by the local community, not only for it’s graceful appointment of the building but also for it’s it’s link to the community’s past and its timekeeping.

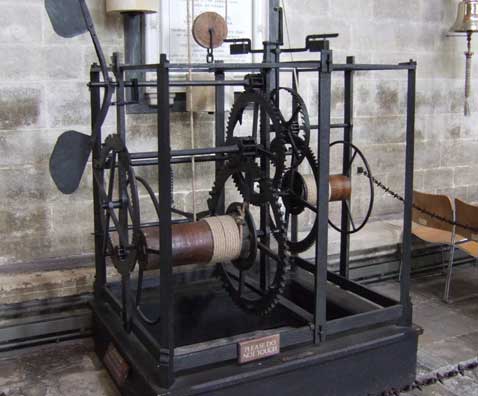

These clocks have provided this service, in church towers throughout the country, for hundreds of years, and in the case of the Ancient Clock of Salisbury Cathedral since 1386. This wonderful mechanism is on display within the nave of the Cathedral, ticking away making it not only the oldest clock in Europe, but the oldest working clock in the World.

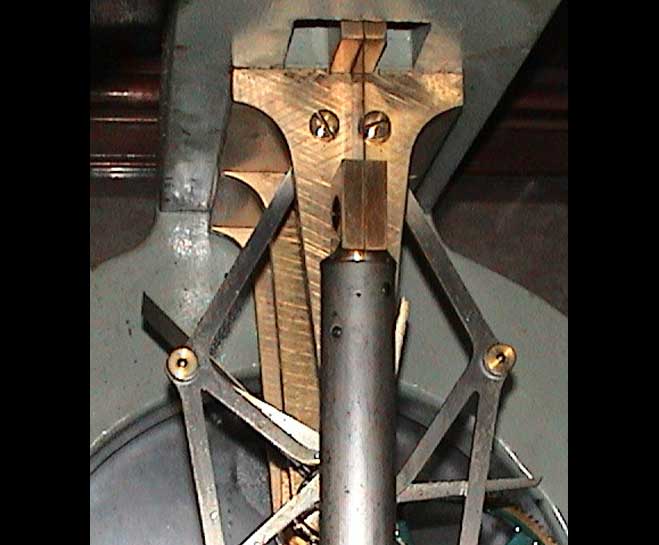

These early turret clocks kept time using a verge and foliot escapement, a mechanism for regulating the rate at which the clock runs, but it wasn’t until advent of the pendulum in 1656 that timekeeping became more reliable.

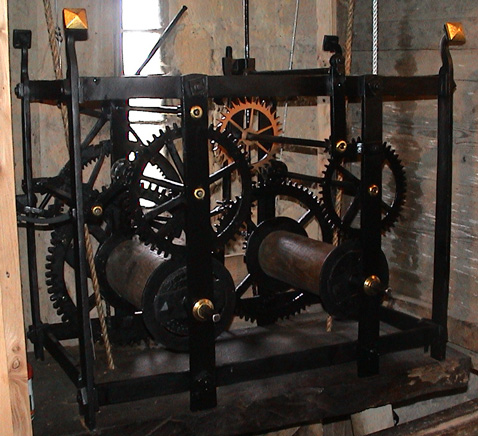

The early examples were manufactured from wrought iron and were often referred to as being blacksmith made, which without doubt they were, but we must not for one moment think that there was anything agricultural about them.

These clocks were the cutting edge of technology at their time and could, and still can, if properly repaired and maintained, keep time to within a few seconds a week.

Because of the growing importance of accurate timekeeping, mainly due to the development of the railways, clockmakers throughout the country strived to keep their clocks accurate whilst combating the problems associated with large dials and hands exposed to the elements.

Because of the growing importance of accurate timekeeping, mainly due to the development of the railways, clockmakers throughout the country strived to keep their clocks accurate whilst combating the problems associated with large dials and hands exposed to the elements.

Different escapements were used such as the recoil and dead-beat, but it wasn’t until Lord Grimthorpe developed his double three legged, gravity escapement in 1859 that large clocks could keep time to within a few seconds a month. His invention was first used on the Westminster clock, better known as Big Ben, and since then a large number of church clocks have been fitted with this escapement.

Throughout the years the church clock has always needed a dedicated person to climb the stairs of the tower, once a week and in some cases every day to wind the heavy weights which keep these wonderful mechanisms working.

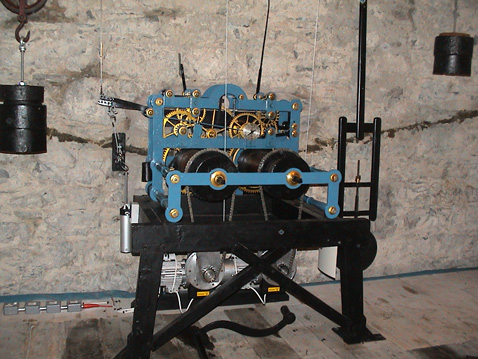

As society has changed it has proved harder to find people willing to take on this responsibility and between 1950 -70 many of these mechanisms were replaced with synchronous electric motors and electric strike and chime units.

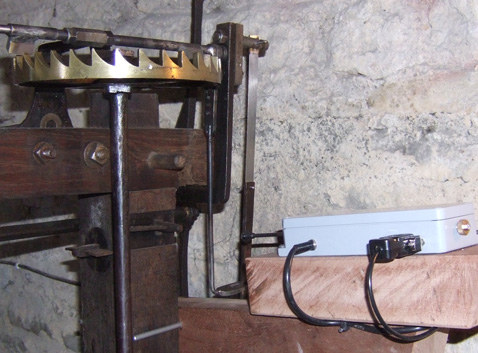

It wasn’t until the Council for the Care of Churches realised that many of our horological treasures were being scrapped and replaced that they stopped this kind of conversion. Since then automatic winding units have been developed to keep the clocks working as they were intended, by removing the chore of having to manually wind them.

However, this same person was responsible to make any minor adjustments to the time indicated by the clock and any small loss or gain could soon accumulate and become an error of 5 or so minutes.

However, this same person was responsible to make any minor adjustments to the time indicated by the clock and any small loss or gain could soon accumulate and become an error of 5 or so minutes.

They would also be responsible for undertaking the summer and winter time change. Because of this auto-regulation systems have been developed, keeping the clock movements to precise time, but ensuring that the integrity of the clock movement stays as it should.

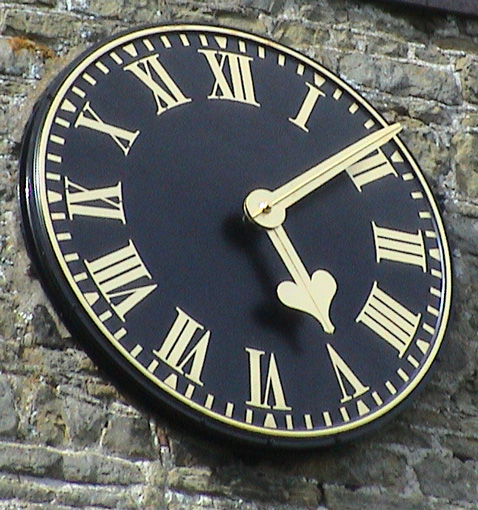

Perhaps the most noticeable aspect of church clock is the dial. At first clocks did not drive dials at all, but indicated the time by striking a bell.

The very first dials only had a single hour hand, with the dial divided into twelve hours and each hour divided into quarters.

It wasn’t until the early 1700’s that dials started to have both an hour and minute hand.

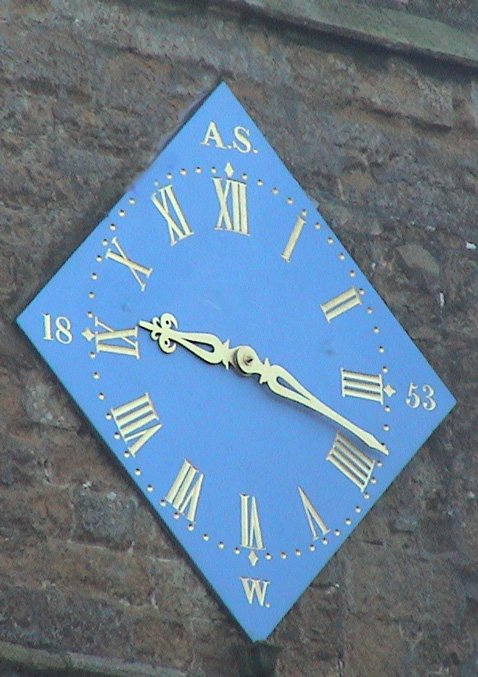

Dials come in all shapes and sizes and manufactured from a vast range of materials.

Dials come in all shapes and sizes and manufactured from a vast range of materials.

The earlier dials are usually manufactured from wood, stone or copper, but as cast-iron became more readily available during the Victorian period, many churches were fitted with glazed skeleton dials which allowed them to be illuminated at night.

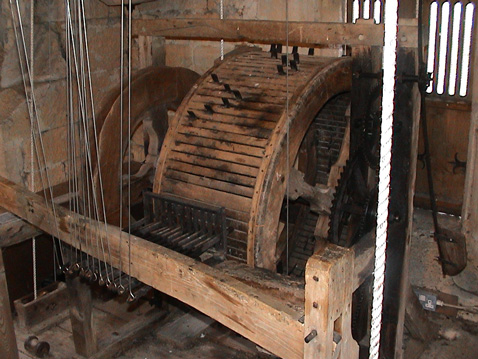

As with domestic or house clocks these larger mechanisms strike and chime the hours and quarters.

A majority strike only the hours, but some indicate the quarters either with the well known Westminster chimes or with a ting-tang. If the tower contains eight or more bells a chime machine or carillon maybe found.

These machines act like large music boxes lifting heavy hammers to strike the bells and play tunes or hymns at intervals throughout the day and night.

Again, as society changes it has proved necessary for night silencing systems to be developed so that in areas which over the years have become more residential the chimes can be silenced to whatever period is acceptable.

It is so important that these magnificent mechanisms are kept in good working order and that their integrity remains intact and that the people entrusted with their care and maintenance are encouraged to treat them with the respect that they deserve. This will ensure that they continue giving faithful service to their respective community’s for many years to come.

And to all those clockmakers involved in their care, I would like to pass on a few words of wisdom given to me by an old clockmaker.

“When working on the clock imagine that the man responsible for its manufacture is sitting behind you, and if he has a smile on his face you’re doing the job right. If not start again or pack your bag”

To find out more about clocks visit www.clockmaker.co.uk